ORIGINAL

Productive performance of naked neck chickens that were fed leaf meal shrubs

Comportamiento productivo de pollos cuello desnudo que se alimentaron con harina de hojas de arbustos

Santos M Herrera G,1* Ph.D, Aslam Díaz C,2 Ph.D.

1Technical University of Quevedo (UTEQ), Faculty of Animal Science, Carretera de Quevedo a Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas, km 1 ½, Quevedo, Los Ríos, Ecuador.

2University of Guayaquil, Faculty of Medicine veterinary and Zootechnics. Kennedy Avenue and Delta, Guayaquil, Guayas, Ecuador.

*Correspondence: mallyhe55@hotmail.com

Received: April 2015; Accepted: August 2015.

ABSTRACT

Objective. To compare the productive performance of naked neck chickens (phases of initiation, growth and final) that were fed meals Gliricidia sepium, Cajanus cajan and Morus alba leaves. Materials and methods. 192 chickens, 1-84 days of age were distributed in a randomized block design with three experimental groups (5% of shrub in the diet), 48 animals/ group, eight replicates/ treatment, six animals/ reply and three animals/ sex in each replicate were used. The control group consumed diet based on corn and soybeans. They were reared on floor. Weighed every seven days. Weight gain, voluntary intake, conversion, balance and efficiency of feed utilization were calculated. Results. The highest total feed intake and average daily gain in rearing were 37.43g 9509.96 g respectively for M. alba (p<0.05), which also presented the best efficiency of energy and protein. Meanwhile, G. sepium showed the lowest values. Conclusions. It is possible to replace 5% of corn and soy in the diet of naked neck chickens, with the inclusion of leaf meal M. alba and get a favorable productive behavior.

Key words:Cajanus, consumption, gain, Gliricidia, Morus, poultry (Source: NAL Agricultural Thesaurus).

Objetivos. Comparar el comportamiento productivo de pollos cuello desnudo (fases de inicio, crecimiento y final) que se alimentaron con harinas de hojas de Gliricidia sepium, Cajanus cajan y Morus alba. Materiales y métodos. Se utilizaron 192 pollos, de 1-84 días de edad que se distribuyeron en un diseño de bloques al azar, con tres grupos experimentales (5% de arbustivas en la ración), 48 animales/ grupo, ocho réplicas/ tratamiento, seis animales/ réplica y tres animales/ sexo, en cada réplica. El grupo control consumió dieta a base de maíz y soya. Se criaron en piso. Se pesaron cada siete días. Se calcularon la ganancia de peso, el consumo voluntario, la conversión, el balance y la eficiencia en la utilización de alimentos. Resultados. El mayor consumo total de alimento y la ganancia promedio diaria en la crianza fueron de 9509.96 g y 37.43g, respectivamente, para M. alba (p<0.05), donde también se presentó la mejor eficiencia en el uso de la energía y la proteína. Mientras, la G. sepium presentó los valores más bajos. Conclusiones. Es posible sustituir el 5% de maíz y soya, en la dieta de pollos cuello desnudo, con la inclusión de harina de hojas de M. alba y obtener un favorable comportamiento productivo.

Palabras clave: Avicultura, Cajanus, consumo, ganancia, Gliricidia, Morus (Fuente: NAL Tesauro Agrícola).

INTRODUCTION

Meals from shrubs leaves such as Gliricidia sepium, Cajanus cajan and Morus alba are alternatives to grains rich in protein and energy, to reduce the cost of feed, in raising monogastric animals (1). G. sepium and C. cajan belong to the Fabaceae or Legumes family and M. alba is Moraceae family. The three plants are cultivated in tropical regions for its high content of protein, energy and minerals (2).

These plants can be used for feeding naked neck camperos chicks considered heterozygous. They tolerate heat better, are more resistant to adverse environmental conditions and increased efficiency in converting nutrients in meat (3).

However, it is necessary to study the productive performance of naked neck chicks, with the inclusion in the diets of shrubs, as a novel alternative, because of its effect is not known in terms of feed consumption and conversion as well as efficiency nutrient use.

The inclusion of 5% leaf meal from M. alba, could improve feed consumption, growth performance and the efficiency of nutrients, compared with the inclusion of G. sepium and C. cajan, which would allow the replacement of corn and soybeans in naked neck chickens diet.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the productive performance of naked neck chickens fed meal from shrubs (Morus alba, Gliricidia sepium and Cajanus cajan), as replacement of corn and soybean in diet.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Location. The research was conducted in the province of Los Ríos, Republic of Ecuador, a 01°06’ south latitude and 79°29’ west longitude, 75 meters above sea level, with an annual average temperature of 24.70°C, relative humidity 87%, average annual rainfall of 2613 mm, annual heliophany of 886 h and clay loam soil.

Planting, harvesting and drying of the plant. M. alba (var. Criolla) and G. sepium planted with cuttings (inclined) of 40 cm, a distance between plants of 40 cm and 1 m between rows, in an area of 5000 m2 which was divided into three batches (1667 m2/ batch) according to the age of the seed (30; 45 or 60 days after regrowth) and fertilized with organic fertilizer (300 kg/ ha/ year). C. cajan will sow 18 kg seed/ ha broadcast, because its objective was as forage. The initial cut was made after one year of establishment. The foliage (leaves and tender stems) were collected manually, dried in the shade, on a cement floor for three days, homogenized, ground and stored for later use in rations, with successive cuts every 45 days.

Chemical analysis of food. The DM, CP, ME, ether extract (EE), NDF, ADF, hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin were determined (4).

Animals and diets. Heterozygous naked neck chickens 192 (T451N), 96 males and 96 females, average weights 50 g at one day of age were used. Were vaccinated against Newcastle. The animals were housed in rustic facilities and raised in floor with a bed of 15 cm chip. The area was divided with fences, to assign the animals to different groups and adapted to diets for 14 days. Birds received the ration once daily. The three experimental groups fed flour foliage shrub (treatments I, II and III) at the level of 5%. The control group consumed a corn and soybean basal diet (Table 1). The rations were formulated according to the requirements for these phases (5). All diets were iso-energetic (11 MJ/kg metabolizable energy DM) and iso-protein (19; 17 and 16% crude protein, to rearing phases I, II and III). The animals had free access to water and food.

Table 1. Composition of diets for phase in naked neck chickens that were fed meals shrubs (5% inclusion).

Experimental procedure. The animals were weighed weekly, at 7:30 am, before feed distribution, to calculate the average daily gain (ADG), phase and accumulated breeding (accumulated in raising body weight is the result of the difference between the final liveweight less 50 g of liveweight purchase of animals, divided by the 84 day of rearing). Birds were placed under heating for seven days. These heaters were connected four hours before the arrival of the animals. In the area of each of the 32 replicates a trough and manual feeder and 60 watt bulb was installed. Voluntary intake (supply-rejection) was measured once a week. Feed conversion and feed intake were calculated from the liveweight gain. The feed balance and the efficient use of energy and protein, to the weight gain obtained were calculated (such as energy and protein intake divided by the average daily live weight gain).

Statistical analysis. The animals were distributed in a randomized block design with three experimental groups (48 animals/ treatment, with 5% shrub in the ration), eight replicates per treatment, six animals per replicate (three animals/ sex) and a group 48 control animals (diet based on corn and soybeans). Data were analyzed by SAS software (Statistical Analysis System), version 9.3 (2013) (6) to evaluate descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) and multiple range test Turkey was used to compare means, in the analysis of variance (ANOVA), to 0.05 significance level.

RESULTS

The greatest total consumption (p<0.05) was obtained in the control (8644.18 g) diet and with M. alba (9509.96 g) and lowest with G. sepium (8557.04 g). Similarly happened in the growth phase. However, there was no difference in initial and final phase (table 2).

Table 2. Feed intake (g / animal), by growth phase, naked neck chickens that were fed with 5% flour bushes.

The highest final live weight (p<0.05) was obtained in M. alba (3194.04 g) and the lowest in G. sepium (2859.48 g), as in the accumulated average gain rearing. There was no difference in average daily liveweight gain in the initial and final phases, but in the growth phase, the best gains were obtained in M. alba and C. cajan (Table 3).

Table 3. Behaviour productive nude neck chickens were fed 5% flour bushes.

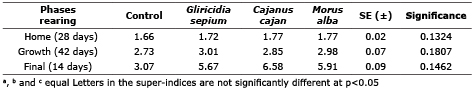

There were no differences in feed conversion in any of the three phases (Table 4).

Table 4. Conversion of nutrients for each phase, in naked neck chickens that were fed with 5% flour bushes.

With the food balance calculation showed that all diets covered the nutritional requirements of chickens to gain weight (Table 5) was obtained. The average chemical composition of flours M. alba, G. sepium and C. cajan were: 92.80; 89 and 94.66% dry matter (DM), 24.80; 22.90 and 25.27% crude protein (CP), 2.96; 1.94 and 1.13% calcium (Ca), 0.38; 0.23 and 0.33% phosphorus (P), 12.68; 27.22 and 39.14% crude fiber (CF) and 7.10; 8.74 and 7.64 MJ/ kg of metabolizable energy (ME). The study of the efficiency the use of energy and protein diet (table 5) reaffirmed the results of the voluntary consumption and better performance of animals fed M. alba (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 5. Balance of food, growth phase, naked neck chickens consuming meals shrubs (5%).

DISCUSSION

A lower consumption of M. alba naked neck chickens heterozygotes, with a value of total consumption of 7420 g, but with 6% inclusión was found (1). The results were higher than M. alba, when 10% leaves and branches were included (7).

This result may be due to increased palatability of M. alba, less fiber and anti-nutritional elements, as opposed to the lower palatability, the increased presence of fiber and antinutritional factors G. sepium and C. cajan (8).

In the leaves of G. sepium have been isolated high in tannins, saponins, coumarins, cyanogenic glycosides, nitrates, protease inhibitor, fitohemoglutininas and phytic acid (9) and C. cajan, high concentrations of amines, phenols, tannins, alkaloids and middle of triterpenes and steroids that affecting the digestibility and voluntary intake.

En las hojas de G. sepium se han aislado altos contenidos de taninos, saponinas, cumarinas, glucósidos cianogénicos, nitratos, inhibidor de proteasas, fitohemoglutininas y ácido fítico (10) y las de C. cajan altas concentraciones de aminas, fenoles, taninos, alcaloides y medios de triterpenos y esteroides (11) que afectan la digestibilidad y consumo voluntario.

Saponins in M. alba were detected and found polyphenols, coumarins and tannins (11). However, the alkaloid content, reducing compounds and tripterpenos was lower. These lend fodder and less bitter taste palatability (8). M. alba has low diversity of secondary structures which are indicative of reduced palatability (1). Nor has high content of flavonoids that cause stunting of animals and digestibility of proteins. These compounds are inhibitors of consumption, foaming properties and interference with intestinal absorption. The species of higher concentrations should be handled with care supply systems, to avoid digestive disorders (12). This could justify the higher consumption of diets with M. alba, regarding G. sepium and C. cajan.

This productive behavior regarding the inclusion of M. alba in poultry diet was positive (13), where the inclusion of 5% mulberry leaf meal in feed for broilers, did not affect weight gain, compared to the control and 968 g were obtained in the startup phase and 955 g in end. With values of 10; 20 and 30% inclusion of M. alba obtained the best results with 10%, but lower than those of this research (7).

Studies in commercial layers with the inclusion of C. cajan showed that the productive behavior was depressed, with increasing flour this plant in the diet, with values over 10% (14).

In all cases the superiority of M. alba diets, to obtain favorable liveweight gains in broiler chickens showed bare neck and at least, this shrub has the potential nutritional necessary to replace part of corn and soybeans in feed for broilers.

Converting the results was positive and no differences were found in control when inclusion levels were low shrub, 3-6% (1). This is likely to be because the four diets had similar nutritional content and value of inclusion of shrub was similar and low in the three treatments, which did not affect the results compared to the control.

Is likely that the inclusion of small amounts of M. alba and the composition of the fiber increase utilization efficiency of the remaining nutrients in the diet (15). This is related to the results in the apparent retention DM, nutrients and low in neutral detergent fiber of M. alba, compared with G. sepium and C. cajan (1).

As for the biological value of the protein and amino acid composition M. alba has higher content of essential amino acids that C. cajan and G. sepium (16-18). This could affect the amino acid balance of birds and limit the efficiency in the utilization of protein in C. cajan and G. sepium as replacers other proteins, which did not happen with M. alba.

However, M. alba diets had the highest efficiency in the use of energy (MJ contribution between CMD) and protein (protein intake between CMD) to increase live weight (average daily gain) for all parenting and stages.

This difference between treatments, their protein-energy or diets should not have been, because all had the same content, but the proportion of soluble and structural carbohydrates and biological value of the protein leading to improved efficiency in the utilization nutrient.

A favorable growth performance, in all cases, by using chickens and improved rustic bareneck was obtained. These animals better tolerate heat, reducing the plumage (19), are more efficient in obtaining greater weight gain, meat yield and mortality is lower. Importantly, in this study only one animal died in the startup phase, by crushing. Regarding the efficiency of the protein, these chickens naked neck protein require 2-3% less than the full plumage, feathers in the formation of regular and silent, and therefore use of these nutrients in the formation of muscle (3).

You can replace 5% of corn and soy in the diet of naked neck chickens, with the inclusion of leaf meal M. alba and get a favorable productive performance, total consumption of 9509.96 g, average daily gain in breeding, 37.43 g efficient use of nutrients, compared with the inclusion of G. sepium and C. cajan.

REFERENCES

1. Herrera SM, Savón L, Lon-Wo E, Gutiérrez O, Herrera M. Inclusion of Morus alba leaf meal: its effect on apparent retention of nutrient, productive performance and quality of the carcass of naked neck fowls. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science 2014; 48 (3): 259-264.

2. Sánchez A. Comportamiento de Aves Ponedoras con Diferentes Sistemas de alimentación. Revista Cubana de Cienciencia Avícola 2009; 33 (1): 11.

3. Fathi M, Elattar A, Ali U, Nazmi A. Effect of the naked neck gene on carcase composition and immunocompetence in chicken. British Poultry Science 2008; 49(2): 103.

4. AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis (19 th) Ass. Off. Anal. Chem. Arligton, VA. Washington, D.C [Internet] 2012. Available in: http://www.worldcat.org/title/official-methods-of-analysis-of-aoac-international/oclc/855542981?referer=di&ht=edition.

5. Santiago RH, Teixeira ALF, Lopes DJ, Cezar GP, Oliveira RF, Clementito LD, Soares FA, Toledo BSL, Frederico ER. Tablas brasileñas para aves y cerdos. Composición de alimentos y requerimientos nutricionales. Viçosa, MG, UFV, DZO, 2011. 259p.

6. SAS. Statistics. vw 9.3. De SAS Institute. INC. Cary. N.C. USA; 2013.

7. Olmo C, Martínez Y, León E, Leyva L, Nuñez M, Rodríguez R, Labrada A, Isert M, Betancur C, Merlos C, Liu G. Effect of Mulberry Foliage (Morus alba) Meal on Growth Performance and Edible Portions in Hybrid Chickens. International Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances 2012; 4(4): 263.

8. Savón L. Harinas de forrajes tropicales. Fuentes potenciales para la alimentación de especies monogástricas. [Tesis Doctoral].La Habana, Cuba, Universidad Agraria de la Habana “Fructuoso Rodríguez Pérez”; 2010.

9. Romero CE, Palma JM, López J. Influencia del pastoreo en la concentración de fenoles y taninos condensados en Gliricidia sepium en el trópico seco. Livestock Research for Rural Development 2010; 12 (4).

10. Paixão A, Mancebo B, Sánchez LM, Walter A, Arsénio de Fontes PAM, Soca M, Roque E, Costa E, Nicolau S. Tamizaje fitoquímico de extractos metanólicos de Tephrosia vogelii Hook, Chenopodium ambrosoides, Cajanus cajan y Solanum nigrum L. de la provincia de Huambo, Angola. Rev. Salud Anim. 2014; 36 (3): 164-169.

11. Albert A, Rodríguez Y. Estudio de los factores antinutricionales de las especies Morus alba Lin (morera), Trichanthera gigantea (h y b), nacedero; y Erythrina poeppigiana (Walp. O. F), piñón para la alimentación animal. Revista Académica de Investigación TLATEMOANI. 2014; 17: 1-15. http://www.eumed.net/rev/tlatemoani/17/tlatemoani17.pdf

12. Álvarez M, García MJ, Belén DM, Medina DR, Muñoz CA, Herrera N, Espinoza C. Evaluación bromatológica de frutos y cladodios de la tuna (Opuntia boldinghii Britton y Rose). Revista Nakari 2009; (17):9-12.

13. Casamachin M, Ortiz D, López J. Evaluación de tres niveles de inclusión de morera (Morus alba) en alimento para pollos de engorde. Revista Biotecnología en el Sector Agropecuario y Agroindustrial 2007; 5 (2): 64-71.

14. Trómpiz J, Rincón H, Fernández N, González G, Higuera A, Colmenares C. Parámetros productivos en pollos de engorde alimentados con grano de quinchoncho durante fase de crecimiento. Revista Facultad de Agronomía (LUZ). 2011; 28 Supl. 1: 565-575.

15. Gonzalvo S, Nieves D, Ly J, Macías M, Carón M, y Martínez, V. Algunos aspectos del valor nutritivo de alimentos venezolanos destinados a animales monogástricos. Livestock Research for Rural Development 2001; 13(2):25.

16. Leyva L, Olmo C, León E. Inclusión de harina deshidratada de follaje de morera (Morus alba L.) en la alimentación del pollo campero. Revista Científica UDO Agrícola 2012; 12(3):653.

17. Miquilena E, Higuera MA. Evaluación del contenido de proteína, minerales y perfil de aminoácidos en harinas de Cajanus cajan, Vigna unguiculata y Vigna radiata para su uso en la alimentación humana. Revista Científica UDO Agrícola 2012; 12 (3): 730-740.

18. Cuervo JA, Narváez W, Hahn C. Características forrajeras de la especie Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Stend, FA BACEAE. Revista Boletín Científico Centro de Museo de Historia Natural 2013; 17 (1): 33-45.

19. Galal A, Ahmed A, Ali UM, Younis HH. Influence of Naked Neck Geneon Laying Performance and Some Hematological Parameters of Dwarfing Hens. International Journal of Poultry Science 2007; 6 (11): 807.