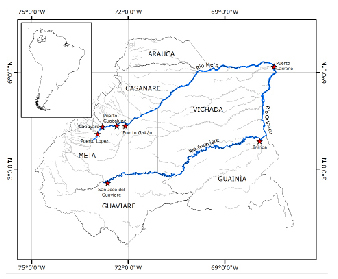

Figure 1. Main landing ports for Zungaro zungaro in the Colombian Orinoco.

ORIGINAL

Spatial and temporal length distribution of Zungaro zungaro caught in the Orinoco River Basin of Colombia

Distribución espacial y temporal de tallas de captura de Zungaro zungaro en la Orinoquia colombiana

Hernando Ramírez-Gil,1 Ph.D.

1Universidad de los Llanos, Faculty of Basic and Engineering Sciences, Department of Basics, Investigation group: Evaluation, handling and conservation of hydrobiological and fishing resources, km 12 Vía Puerto López, Vereda Barcelona, Villavicencio, Meta, Colombia.

*Correspondence: hramirezgil@gmail.com

Received: February 2014; Accepted: March 2015.

ABSTRACT

Objective. To determine the effect of fishing on capture size of both male and female Zungaro zungaro catfish, historical records of size and spatial distribution of the species were analyzed from the Orinoco Basin in Colombian. Materials and methods. Information was collected by sampling fishing port landings in the region between 1979 and 2011. Each specimen was measured, weighed and sexed. With 5411 records, the average size at capture were compared in time and among the different ports. Size at 50% maturity was estimated by quinquennium. Results. The average commercial capture sizes of Z. zungaro ranged from 35 to 161 cm standard length, with differences between males and females. From 1979 to 2011, in Puerto Lopez, the size at sexual maturity decreased from 123.8 to 83.4 cm in females and from 93.3 to 61 in males. In the annual cycle the greater average capture size in females was from April to July and for males from May to June. Average annual length is higher in the higher parts of the Meta and Guaviare river drainages. In the last quinquennium the size at 50% maturity had fallen 10 cm in females and 5 cm in males and it is higher than the average capture size. Conclusions. Populations of Z. zungaro in the Colombian Orinoco River Basin have been affected by overfishing and selective fishing of females.

Key words: Overfishing, population dynamics, river fisheries, sexual selection (Source: ASFA).

RESUMEN

Objetivo. Determinar el grado de afección en la población de Zungaro zungaro a partir del análisis del comportamiento histórico y espacial de las tallas de captura de hembras y machos de la especie en la Orinoquia colombiana. Materiales y métodos. La información fue colectada mediante muestreos a los desembarcos en puertos pesqueros de la región entre 1979 y 2011. Cada ejemplar fue medido, pesado y sexado. Con 5411 registros, se estableció la distribución de las tallas medias de captura, que se compararon en el tiempo y entre los diferentes puertos. Se estimó la talla de madurez gonadal (TMG) por quinquenios. Resultados. El rango de las tallas de captura comercial Z. zungaro fue de 35 a 161 cm longitud estándar (LS), con diferencia entre machos y hembras. Entre los años 1979 a 2011, en Puerto López, la talla promedio de captura anual (LS) disminuyó de 123.8 a 83.4 cm en hembras y de 93.3 a 61 cm en machos. En el ciclo anual la mayor talla promedio de captura de hembras se presenta en abril a julio y de machos en mayo y junio. La talla promedio de captura anual (TPCA) es superior en las partes altas de los ríos Meta y Guaviare. En el último quinquenio la TMG ha disminuido 10 cm en las hembras y cinco cm en los machos y es superior a la TPCA. Conclusiones. Hay afectación sobre la población explotada de Z. zungaro por sobrepesca por crecimiento y pesca selectiva de hembras en la Orinoquia colombiana.

Palabras clave: Dinámica de poblaciones, pesca fluvial, selección sexual, sobrepesca, (Source: ASFA).

INTRODUCTION

The Zungaro genus belongs to a commercially used group of catfish that reaches large sizes (1), distributed in the basins of the Orinoco (2-4), Amazonas (5) and Parana Rivers, Paraguay (1). The species is characterized by reproductive migration in one annual spawning period with high relative fertility, free eggs without parental care, and rapid embryogenesis (6). In the Orinoco Z. zungaro (4,7,8), it occupies the second place in size within the group of big catfish with females reaching a standard length of 165 cm (LS) and males with lengths reported up to 138 cm LS (2). Size of gonadal maturity was estimated in the upper Rio Meta at 127 cm LS for females and 107 cm for males (2). In the Orinoco it has two annual migrations, the first reproductive one in the months of March to June and the second for food from September to December (2). In addition, the intrinsic value of the species, as it holds great social and economic importance in food security for the coastal population of the Arauca, Meta, Guaviare and Orinoco Rivers, and given its high price in the market it is part of a value chain that goes from the fisherman to the major consumer centers.

In 2009 commercial quantities of Z. Zungaro in the Colombian Orinoco were in fourth place among the fish species sold in the region, with a contribution of 86 t (2). Annual landings have declined, for example in Puerto Lopez, they went from 50 t in 1985 to 32.3 t in 2009 (2). This decline in landings as well as the large specimens found, the migratory nature of the species and the lack of a conservation program, led it to be included in the Red Book of freshwater fishes of Colombia 2012, in the category of vulnerable (9). This study was done in order to determine if fishery is affecting a population under fishing pressure by analyzing the historical and spatial behavior of catch sizes of males and females of the species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Area of study. The information for this study was collected in the principal landing centers of Z. zungaro in the Colombian Orinoquia.

Río Meta: Puerto López (4°05’N and 72°57’O), Cabuyaro (4°18’N and 72°48’O), Puerto Guadalupe (4°20’N and 72°21O), Puerto Gaitán (4°20’N and 72°05’O) and Puerto Carreño (4°11’N and 67°28’O).

Río Guaviare. San José del Guaviare (2°34’N and 72°38’O), Inírida (3°52’N and 67°55’O), as can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1. Main landing ports for Zungaro zungaro in the Colombian Orinoco.

Field phase. Information was obtained from samples taken at landings. Each specimen was measured (LS) with a 0.01m tape measure, weighed (gutted) with a 100 kg capacity scale with 0.5 kg approximation, macroscopically sexed and classified as immature or mature; a male was considered to be mature when pressed gonads released sperm and a female had visible eggs.

Information was taken at different times, with a monthly sampling in Puerto Lopez between 1979 and 1986, Cabuyaro from 1987-1990 and 1992-1995, and Puerto Guadalupe in 1989, 1990, 1993 and 1994, in Puerto Gaitán with two monthly monitoring times from 1999-2001. In the period from 1987-2003, four monthly surveys were done in Puerto Lopez. Data from 2007 to 2011, with daily sampling efforts in Puerto Lopez, Puerto Gaitán, Puerto Carreño, San José del Guaviare and Inírida, belong to the database of the Fisheries and Aquaculture Sector, provided by the management for Fisheries and Aquaculture of the National Institute of Rural Development - INCODER and the National Authority for Aquaculture and Fisheries - AUNAP.

Given the proximity of Puerto Lopez, Cabuyaro, Puerto Guadeloupe and Puerto Gaitán, length data collected in these collection centers were grouped into just one report to facilitate analysis and are herein designated Upper Meta River.

Average capture size. 5411 records were analyzed to find variations in the distribution of average size in time and space. The historical record of the Upper Meta River from 1979 to 2011 was consulted, and in space the average size found in the different collection centers along the Orinoco was used. To establish whether there were significant differences in size between the sexes as well as between and within yearly cycles and spatially, Levene’s test was applied to establish whether there was homoscedasticity variance for later parametric tests (ANOVA and Tukey) or nonparametric (Kruskall Wallis and Mann-Whitney) as appropriate, using the SigmaPlot 11 (Jandel) statistical package with α=0.05 significance.

Temporal analysis was based on records obtained in Puerto Lopez (upper Meta River) in 30 years of follow-up work.

Size at maturity. LS data for mature males and females were compared using the Student t statistic test to establish whether there were significant differences between records of both sexes. The size of gonadal maturity was calculated for females (n=2372) and males (n=1821), grouping data by quinquennium. At every quinquennium, 30 class marks were established and for each one an absolute, relative and accumulated frequency was estimated. The relative cumulative frequency was linearized (TFRA) using the equation:

![]()

From the lineal regression between the class mark and this transformation, a and b parameters were estimated in the logistics curve:

![]()

Where gonadal maturity (TMG) is considered the size at 50%, measurement that was used to make comparisons between quinquennium.

RESULTS

Commercial catch sizes of Z. Zungaro in the Colombian Orinoco were within a range of 35 to 161 cm LS, with significant differences (p<0.05) between males and females. Variations in average catch sizes were evident in both time (within the hydrological and interannual cycle), and space, considering their geographic distribution.

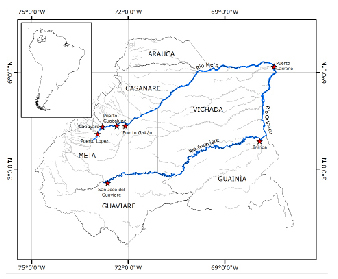

Average capture size. In Puerto López from 1979-2011 the average annual catch size was between 123.8±7.6 cm LS in 1991 and 83.4±29.2 cm in 2011 for females and between 93.3±22 in 1997 and 61±16 cm in 2011 in males. In figure 2 a gradual tendency to diminish in size can be observed in the average annual catch sizes of the males in comparison with the females; in the first 15 years of records (1979 a 1993) the average difference in this parameter between the two sexes was 35.8±8.1cm, which decreased to 23.4±7.2 cm over the next 10 years (1994-2002) and finally reached 17.7±4.2 cm in the last seven years (2005–2011). This behavior was due to a decrease over time of the average annual capture size of females.

Figure 2. Average sizes (LS cm) and standard deviation of Z. zungaro catches (males and females) in Puerto Lopez. Period 1979-2011.

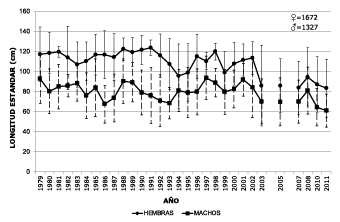

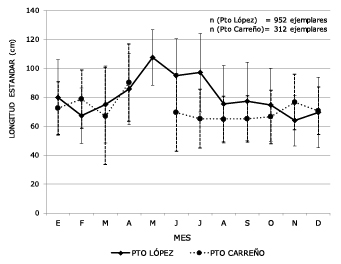

Within the hydrological cycle, the behavior of the average size of monthly catch (TPCM) in the upper Meta River (Figure 3) was analyzed, and significant differences (p<0.05) were found in the size of females captured April to July (between 113 and 124 cm LS) with respect to the other months of the year (between 74 and 102 cm LS). This dynamic was also observed in males for the months of May and June (p<0.05), with significantly higher sizes (between 75 and 109 cm LS) than in the rest of the annual cycle (between 62 and 73 cm). The season with largest sizes coincides with the breeding season of the species in the period of rising waters.

Figure 3. Average size of monthly catch of Z. zungaro males and females in the upper Meta River throughout the water cycle (average 1979-2011).

To analyze the spatial distribution of sizes between collection centers, total population records landed in each port in the years 2007 to 2011 were grouped together. When comparing the two ports of the Meta River, Puerto Lopez at the top and Puerto Carreño at the bottom, no difference (p>0.05) in average monthly catch size was found (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Comparison of average monthly catch sizes in Puerto Lopez and Puerto Carreño (2007,

2008, 2010, 2011). In May there are no records in Puerto Carreño due to the closure

period.

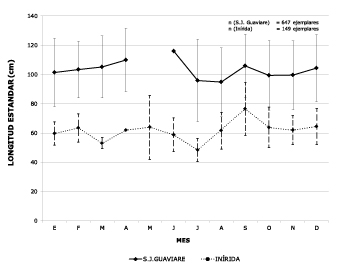

In contrast with the Guaviare River, sizes of fish caught in San José del Guaviare (upper part) were significantly higher (p<0.05) than those in Inírida (lower part), as seen in figure 5. The TPCA of females in San José del Guaviare during the period studied was 102.9±26.8 cm LS and that of males 78.9±24.6 cm, while in Inírida it was 59.5±8.8 cm in females and 68±9.1 cm in males.

Figure 5. Monthly comparison of average catch sizes marketed in the upper Guaviare River (San

Jose) and the lower area (Inírida). Period: 2007, 2008, 2010, 2011.

Size at gonadal maturity (TMG). The size at gonadal maturity for Z. Zungaro females was significantly different from that of males (p<0.05), so that the results are reported by sex.

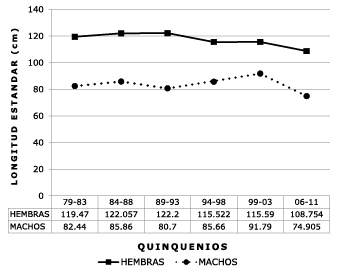

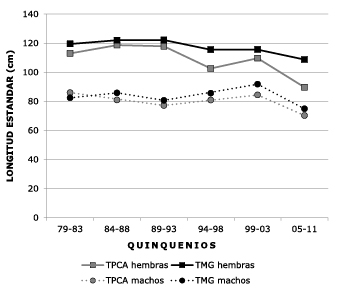

In the Upper Meta River the reported data over 30 years was grouped and the TMG was estimated in quinquennium, as shown in figure 6.

Figure 6. Historical variation for five year periods (30 years) of the sizes at gonadal maturity of

Z. zungaro males and females in the upper Meta River.

From 1979-1993 the TMG of females remained stable and above 119 cm LS, and from that year dropped ten centimeters to settle around 109 cm in 2006-2011. In males the size at maturity was recorded at over 80 cm LS, but in the last five years decreased to 75 cm, which is normal behavior in commercially exploited fish stocks.

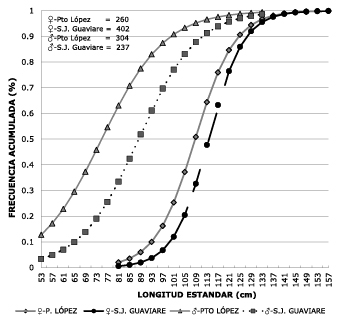

Comparing the estimates of TMG of fish landed in the upper parts of the Meta and Guaviare Rivers (Puerto Lopez, last quinquennium, and San José del Guaviare), we observed that in the Meta River this measurement was lower in females (108.8 cm LS) and males (74.9 cm) than in the group in the Guaviare River where the TMG of females was 113.6 cm LS and that of males was 88.3 cm (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Spatial variation of length at gonadal maturity (TMG) of Z. zungaro males and females between the upper parts of the Meta and Guaviare (2007-2011) rivers.

In the period studied, the average annual catch size of females has been below the TMG over time (Figure 8), accentuating the difference in the last five years. In males in the first five years the TPCA analyzed was superior to TMG and in the following quinquenniums the dynamics were reversed; however, the value of these two parameters was very close.

Figure 8. Comparison of size at gonadal maturity and average catch size at five-year periods in the upper Meta River.

At the head of the Guaviare River the TPCA of females (102.9 ± 26.8 cm LS) is less than the TMG (108.8 cm LS), in males the TPCA (78.9 ± 24.6 cm LS) is lower than TMG (88.3 cm).

DISCUSSION

Average catch sizes. The difference between the size of females and males found in this study is consistent with the report of sexual dimorphism indicating higher growth rates in females than in males (2). Females reach sizes of up to 165 cm LS and males 138 cm (2), higher than those reported for river Z. jahu in the Cuaibá River (Paraguay River Basin) of 163 cm in length (10). According to historical results found in this study, a progressive decrease is observed in the average size of captured females and males, with a sharp drop from 2005 to 2011 as a result of the inevitable effect that fisheries have when they remove larger or older fish from the population (11-13).

When there is a difference in size between the two sexes, larger fish are more vulnerable to fishing pressure and a decrease in the size of that sex is more noticeable (11), which was clearly evident in the case Z. zungaro in the upper Meta, where fishing selectivity directed towards females was reflected in the reduction of the average size of catch, greater in females.

Also variations were observed in the average monthly catch size. Larger sizes were found in the months corresponding to the reproductive period of the species, April to June (2), when the nets select especially females due to increased circular perimeter because of enlarged gonads, increasing mortality for this population group, as has been described for other fisheries (14).

Fisheries exploit the population according to their size frequency distribution (15), and larger sizes of Z. zungaro were reported in the upper parts of rivers where adults and minors are concentrated and in the lower parts where juveniles are found. Reproductive migration of adults has been seen towards the headwaters of the Arauca, Meta and Guaviare (2) rivers, but not of juveniles that, it is assumed, gradually head upriver but not in bulk. This move upstream of juveniles with sizes above 35 cm would primarily be related to migration of bocachico, Prochilodus mariae, their main food and other prey that are not as abundant as Mylossoma duriventre, Leporinus sp., Astyanax spp. and Triportheus ssp. (during the period of falling and low water), when they leave the lagoons and flooded areas to go upriver.

Z. Zungaro is thought to make short migrations that could be similar to Z. jau, in which a linear path of 31.4 km was estimated over a year (16), since they are usually found in the main channel of rivers and whitewater pipes, in deep depressions below wooded sections or waterfalls (2, 16), where they wait for their food to pass by, without having to chasse prey, hence the morphological appearance of robust structure and an almost square head, which differs in body frame when compared with other large migratory catfish of the same group.

Size of gonadal maturity. The TMG of females has declined since 1994-1998, a situation that increased from 2006-2011; TMG in males was higher than 80 cm LS, but in the last five years (2006-2011) it decreased significantly, suggesting that the effects of fishing, larger and older individuals are declining in population, resulting in early maturity of fish at smaller sizes, as has been reported in other fisheries (10, 11, 13, 17, 18, 19). This can also affect the reproductive period, as this tends to be wider seasonal and spatially with parental at older ages when compared to younger (13).

The decrease in TMG adversely affects the rate of population growth by eliminating fish that have high reproductive value (11, 19), since size is affected by maternal size, as has been amply demonstrated, since longer and older females produce larger and stronger eggs and larvae, with a greater chance of survival than those of younger females (11, 13, 20). Reproduction at younger ages and smaller sizes reduces fertility (20), resilience to environmental change (17, 19), and increases the sensitivity of larvae to climate variations, which increases sensitivity of recruitment to changes due to climate (13).

Spatial results also indicate that females and males of the upper Guaviare River maintain a TMG greater than those recorded in the upper Meta River. Fishery in the upper Guaviare River is relatively recent, since geographical isolation and public order problems have limited its development, in contrast to the more than 50 years of fishing tradition in the upper Meta River. Even so, the TMG of females in upper Guaviare River is less than what the historical records indicate in the upper Meta River in 2006-2011, showing that as in Meta, in that area high pressure is being exerted on fish specimens of larger size, the females.

It is clear that historically and spatially the TPCA of females was lower than the TMG, which means that fishing pressure has been exerted on specimens that did not reach TMG, which is considered the optimum catch length, which suggests that overfishing relative to growth exists. Additionally, the TPCA is below the 10th percentile of the maturity curve in Puerto López and in the 30th percentile in San José del Guaviare, which may result in the low numbers of this sex that can reproduce at least once before they are caught, jeopardizing the stability of the species in the basins of the Meta and Guaviare rivers.

In conclusion, the negative impact of fisheries on the species was noted, which may affect future productivity due to declines in recruitment and in the rate of population growth, given that overfishing and selective fishing of adult females is a practice. Extending the closure period of three months starting in April is recommended to facilitate migration and increase parental reproductive success of the species in the area. The significant difference in size between males and females in the TMG Z. zungaro, as well as the dynamic variation of this parameter in the population over time, demonstrates the urgent need to directly monitor and record catches and individualized long-term analysis by gender that will help detect and establish measures to ensure a sustainable exploitation of this resource.

REFERENCES

1. Boni TA, Padial AA, Prioli SMAP, Lucio LC, Maniglia TC, Bignotto TS et al. Molecular differentiation of species of the genus Zungaro (Siluriformes, Pimelodidae) from the Amazon and Paraná-Paraguay River basins in Brazil. Genet Mol Res 2011; 10(4):2795-2805.

2. Lasso CA, Agudelo-Córdoba E, Jiménez-Segura LF, Ramírez-Gil H, Morales-Betancourt M, Ajiaco-Martínez, et al (Editores.) I. Catálogo de los Recursos Pesqueros continentales de Colombia. Serie Editorial Recursos Hidrobiológicos y Pesqueros continentales de Colombia. Bogotá, D.C., Colombia: Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt (IAvH). 2011; 537-541.

3. Machado-Allison A, Bottini B. Especies de la pesquería continental venezolana: un recurso natural en peligro. Bol Acad C Fís Mat y Nat 2010; 70(1):59-75.

4. Pérez-Lozano A, Barbarino A. Parámetros poblacionales de los principales recursos pesqueros de la cuenca del río Apure, Venezuela (2000-2003). Lat Am J Aquat Res 2013; 41(3):447-458.

5. Agostinho AA, Pelicice FM, Gomes LC. Dams and the fish fauna of the Neotropical region: impacts and management related to diversity and fisheries. Braz J Biol 2008; 68(4):1119-1132

6. Godinho AL, Reis I, Godinho H. Reproductive ecology of Brazilian freshwater fishes. Environ Biol Fish 2010; 87:143–162

7. Maldonado-Ocampo JA, Vari RP, Usma JS. Checklist of the freshwater fishes of Colombia. Biota Colombiana 2008; 9(2):143-237.

8. Lasso C, Usma JS, Villa F, Sierra-Quintero MT, Ortega-Lara A, Mesa LM, et al. Peces de la Estrella Fluvial Inírida: ríos Guaviare, Inírida, Atabapo y Orinoco, Orinoquía colombiana. Biota Colombiana 2009; 10(1-2):89–122.

9. Mojica JI, Usma JS, Alvarez-León R, Lasso CA (Editores). Libro rojo de peces dulceacuícolas de Colombia. Bogotá, D. C., Colombia: Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia, WWF Colombia, Universidad de Manizales. 2012; 192-195.

10. Mateus LAF, Penha JMF. Dinâmica populacional de quatro espécies de grandes bagres na bacia do rio Cuiabá, Pantanal norte, Brasil (Siluriformes, Pimelodidae). Rev Bras Zool 2007; 24(1):87-98.

11. Fenberg P, Roy K. Ecological and evolutionary consequences of size-selective harvesting: how much do we know? Mol Ecol 2008; 17:209-220

12. Longhurst A. The sustainability myth. Fish Res 2006; 81:107–112

13. Perry RI, Cury P, Brander K, Jennings S, Möllmann C, Planque B. Sensitivity of marine systems to climate and fishing: Concepts, issues and management responses. J Mar Syst 2010; 79(3):427-435.

14. Rijnsdorp AD, Grift RE, Kraak SBM. Fisheries-induced adaptive change in reproductive investment in North Sea plaice (Pleuronectes platessa)? Can J Fish Aquat Sci 2005; 62(4):833-843.

15. Enberg K, Jørgensen C, Dunlop E, Varpe O, Boukal D, Baulier L et al. Fishing-induced evolution of growth: concepts, mechanisms and the empirical evidence. Mar Ecol 2012; 33:1–25.

16. Alves CBM, Silva LGM, Godinho AL. Radiotelemetry of a female jaú, Zungaro jahu (Ihering, 1898) (Siluriformes: Pimelodidae), passed upstream of Funil Dam, rio Grande, Brazil. Neotrop Ichthyol 2007; 5:229-232.

17. Jørgensen C, Enberg K, Dunlop ES, Arlinghaus R, Boukal DS, Brander K, et al. Ecology-Managing evolving fish stocks. Science 2007; 318(5854):1247-1248.

18. Heino M, Baulier L, Boukal DS, Ernande B, Johnston FD, Mollet FM et al. Can fisheries-induced evolution shift reference points for fisheries management? ICES J Mar Sci 2013; 70:707–721.

16. Laugen AT, Engelhard GH, Whitlock R, Arlinghaus R, Dankel DJ, Dunlop ES et al. Evolutionary impact assessment: accounting for evolutionary consequences of fishing in an ecosystem approach to fisheries management. Fish Fish 2014; 15:65–96

17. Venturelli PA, Shuter BJ, Murphy CA. Evidence for harvest-induced maternal influences on the reproductive rates of fish populations. Proc Biol Sci 2009; 276(1658):919-924